5 madonnas in exile

Multimedia Site-Specific Installation

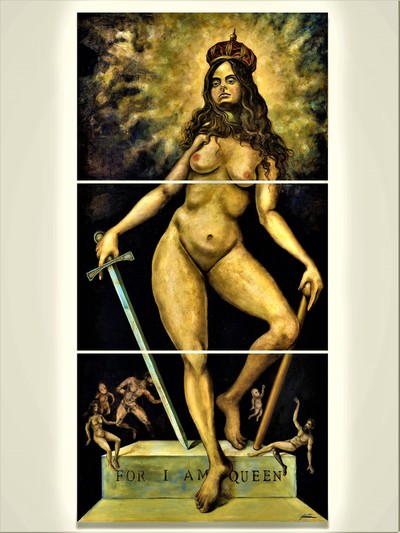

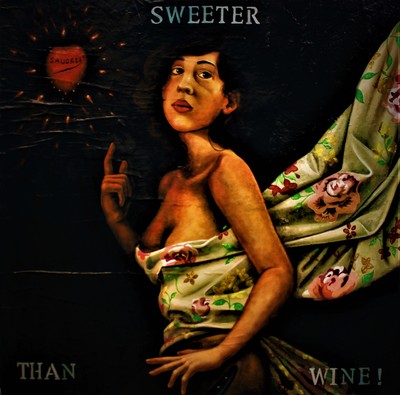

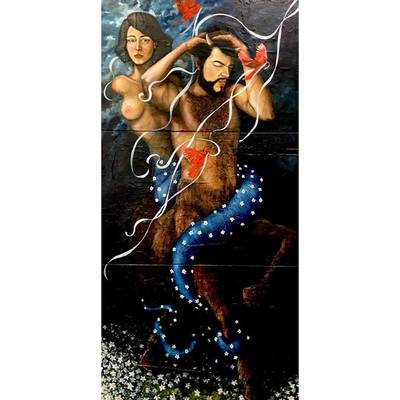

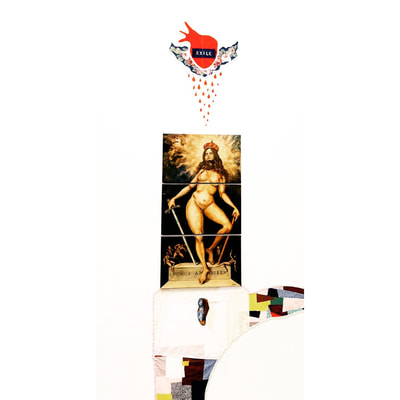

5 Madonnas in Exile is a multimedia, audience-participatory, and site-specific exhibit that aims to highlight the plight of immigrants and asylum seekers through a symbolic and multidimensional language. Here, Jônatas draws parallels between his family's long history of immigration, the role that specific women have played in keeping the family together, and the current global immigration crisis.

The artist's Madonnas are inspired by his Sephardic female ancestors who were exiled and during the pogroms of Inquisitional Spain and Portugal (15th to 18th century). These women would end up occupying a variety of important roles: passing down their fragmented traditions to the next generation, and making sure the family unit did not crumble while in exile. These women were also the main spiritual, educational, and business leaders of their migratory communities.

Due to their communal importance, most of these females were addressed by the title of Dona (female for Don, a title of honor), which is customary in Iberian and Latino societies. For Jônatas, however, the title of Dona brings to mind yet another word; Madonna. This word is used only when referring to a highly virtuous woman, usually idealized by the Catholic Church through the image of Mary.

Jônatas feels that it is appropriate to not only call his exiled heroines by the title of Dona, but also by the title of Madonna, for they achieved virtuosity through high altruism and a deep trust in the improbable. It is through them that Jônatas introduces the flow of his exhibit:

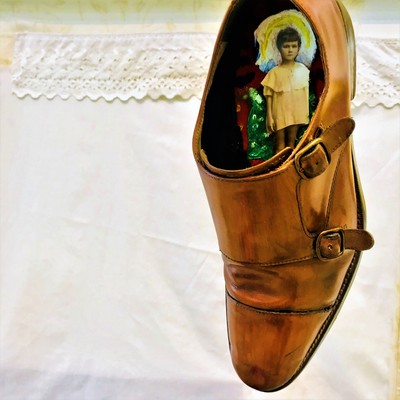

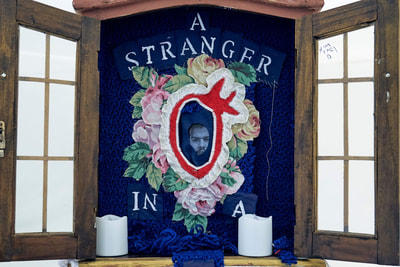

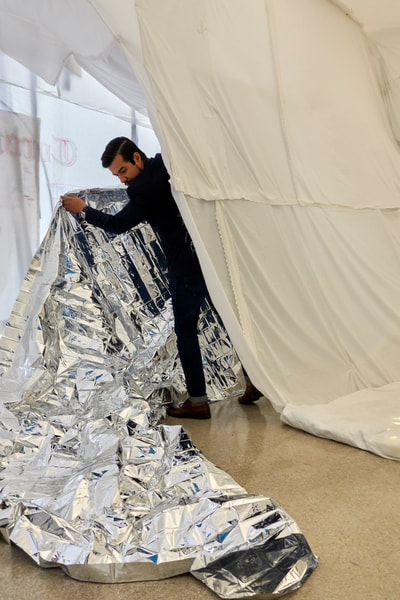

As a fabric pathway spreads throughout the exhibition floor and ceiling from a small brown-leather suitcase into a large fabric cathedral installation, the viewer is guided to each of the Madonnas and their corresponding stage between Exile and Redemption.

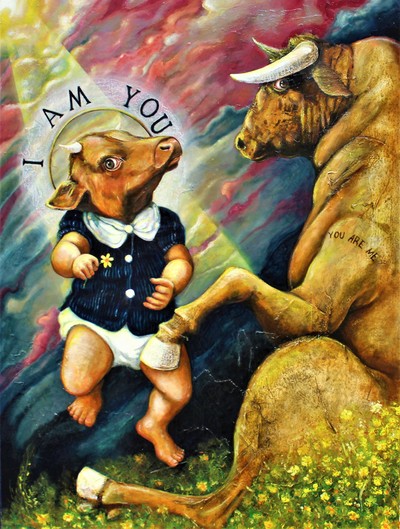

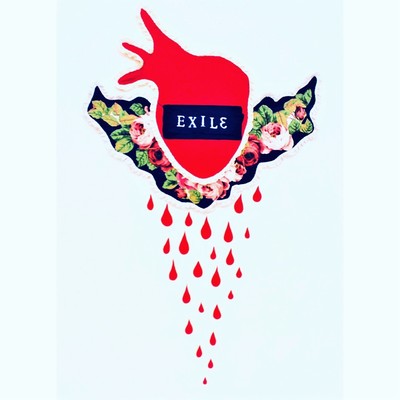

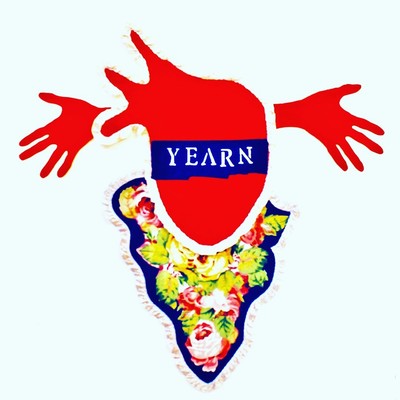

The five archetypal women signify Exile, Memory, Yearning, Repentance, and Redemption. The two other major elements of the exhibit are the bull figure and a fabric cathedral installation, relate to the five Madonnas and to the exhibit’s subtitle, The Refugee Cathedral of the Ascending Bull.

Here, Jônatas borrows two of the strongest visual elements of Iberian culture: the Church and the bull. By doing so he is able to revisit his family's history of trauma with the Church, and to talk about the cattle-like treatment that Conversos received in Spain and Portugal. Likewise, Jônatas warns that immigrants in the United States and Europe are currently receiving a similar treatment.

The ever-reliable cattle is willing to provide necessary strength at a very low cost, but in times of euphoria, upheaval, and famine, it is often sacrificed in slaughter houses or the bull-fighting arena. Similarly, immigrants are often appreciated at times of bountifulness and peace, but in moments of crisis are singled out and sacrificed in the political arena, sometimes not only rhetorically.

As for the cathedral, when one enters it, one is confronted by yet another related element, a spiraling fabric maze. This further emphasizes the disorienting experience of being in exile, and living in between conflicting worlds.

At the end of this maze there is an altar, where several screens show Jônatas migrating on a raft, drifting for hours between water channels and the open ocean. Jônatas is wearing a suit and a bow-tie, signifying composure in the face of the unknown. Only by wrapping himself on a large piece of fabric, which he wets in the ocean, is Jônatas able to continue his journey in the 110 Degree (Fahrenheit) heat.

Sojourning through water brings to mind that most asylum-seeking immigrants arrive in other countries via the ocean. This is specially true in the case of Cubans and Haitians who arrive to Miami, the artist's Home-State in the U.S.

Just like in any other temple, the ultimate goal of this fabric cathedral is to be a place where one may enter to pay reverence to something greater than oneself – such as one’s ancestral history, or by connecting to one’s faith-tradition.

Deep within this fabric sanctuary, one is reminded of what these five Madonnas seemed to be clearly aware of; that alone we are nothing but threads, but together we can be as strong as the very fabric of society.

The artist's Madonnas are inspired by his Sephardic female ancestors who were exiled and during the pogroms of Inquisitional Spain and Portugal (15th to 18th century). These women would end up occupying a variety of important roles: passing down their fragmented traditions to the next generation, and making sure the family unit did not crumble while in exile. These women were also the main spiritual, educational, and business leaders of their migratory communities.

Due to their communal importance, most of these females were addressed by the title of Dona (female for Don, a title of honor), which is customary in Iberian and Latino societies. For Jônatas, however, the title of Dona brings to mind yet another word; Madonna. This word is used only when referring to a highly virtuous woman, usually idealized by the Catholic Church through the image of Mary.

Jônatas feels that it is appropriate to not only call his exiled heroines by the title of Dona, but also by the title of Madonna, for they achieved virtuosity through high altruism and a deep trust in the improbable. It is through them that Jônatas introduces the flow of his exhibit:

As a fabric pathway spreads throughout the exhibition floor and ceiling from a small brown-leather suitcase into a large fabric cathedral installation, the viewer is guided to each of the Madonnas and their corresponding stage between Exile and Redemption.

The five archetypal women signify Exile, Memory, Yearning, Repentance, and Redemption. The two other major elements of the exhibit are the bull figure and a fabric cathedral installation, relate to the five Madonnas and to the exhibit’s subtitle, The Refugee Cathedral of the Ascending Bull.

Here, Jônatas borrows two of the strongest visual elements of Iberian culture: the Church and the bull. By doing so he is able to revisit his family's history of trauma with the Church, and to talk about the cattle-like treatment that Conversos received in Spain and Portugal. Likewise, Jônatas warns that immigrants in the United States and Europe are currently receiving a similar treatment.

The ever-reliable cattle is willing to provide necessary strength at a very low cost, but in times of euphoria, upheaval, and famine, it is often sacrificed in slaughter houses or the bull-fighting arena. Similarly, immigrants are often appreciated at times of bountifulness and peace, but in moments of crisis are singled out and sacrificed in the political arena, sometimes not only rhetorically.

As for the cathedral, when one enters it, one is confronted by yet another related element, a spiraling fabric maze. This further emphasizes the disorienting experience of being in exile, and living in between conflicting worlds.

At the end of this maze there is an altar, where several screens show Jônatas migrating on a raft, drifting for hours between water channels and the open ocean. Jônatas is wearing a suit and a bow-tie, signifying composure in the face of the unknown. Only by wrapping himself on a large piece of fabric, which he wets in the ocean, is Jônatas able to continue his journey in the 110 Degree (Fahrenheit) heat.

Sojourning through water brings to mind that most asylum-seeking immigrants arrive in other countries via the ocean. This is specially true in the case of Cubans and Haitians who arrive to Miami, the artist's Home-State in the U.S.

Just like in any other temple, the ultimate goal of this fabric cathedral is to be a place where one may enter to pay reverence to something greater than oneself – such as one’s ancestral history, or by connecting to one’s faith-tradition.

Deep within this fabric sanctuary, one is reminded of what these five Madonnas seemed to be clearly aware of; that alone we are nothing but threads, but together we can be as strong as the very fabric of society.